|

Introduction

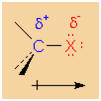

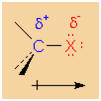

An alkyl

halide is another name for a halogen-substituted

alkane. The carbon atom, which is bonded to the halogen

atom, has sp3 hybridized bonding orbitals and

exhibits a tetrahedral shape. Due to electronegativity

differences between the carbon and halogen atoms, the σ

covalent bond between these atoms is polarized, with the

carbon atom becoming slightly positive and the halogen atom

partially negative. Halogen atoms increase in size and

decrease in electronegativity going down the family in the

periodic table. Therefore, the bond length between carbon

and halogen becomes longer and less polar as the halogen

atom changes from fluorine to iodine.

POLARITY AND STRENGTH OF THE CARBON-X BONDS

-

Carbon-halogen bonds are very substantially polar

covalent, with carbon as the positive and halogen as the

negative end of the dipole. Conosequently, the carbon

attached to the halogen is electrophilic. We

shall see in the next chapter how nucleophiles react at

the carbon of an alkyl halide.

-

The carbon-fluorine bond is the strongest, especially

since fluorine is the most electronegative of the

halogens, resulting in a larger contribution of the

polar (ionic) structure to the resonance hybrid. The

larger contribution of the ionic structure not only

makes the molecule more polar, it also makes the bond

more stable because the ionic structure is lowered in

energy. However, all of the C-X bonds are significantly

polar.

-

The C-X bond dissociation energies (D), which you do not

need to memorize, are C-F 108; C-Cl 85; C-Br 70; C-I 57

(these are for CH3-X bonds).

NOMENCLATURE

Alkyl halides are named using the

IUPAC rules for alkanes. Naming the alkyl group attached to

the halogen and adding the inorganic halide name for the

halogen atom creates common names.

-

Essentially, the naming of alkyl halides is not

different from the naming of alkanes. The halogen

atoms are treated as substituents on the main chain,

just as an alkyl group, and have no special priority

over alkyl groups.

-

The name of a chlorine substituent is "chloro", that

of a bromine substituent "bromo" and so on.

-

You sould practice naming a variety of haloalkanes.

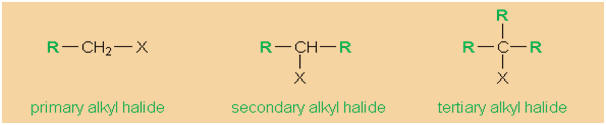

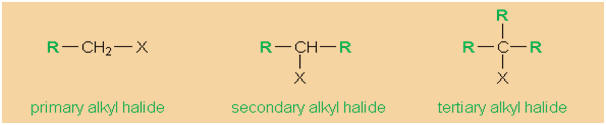

Alkyl halides may formally be derived from alkanes

by exchanging hydrogen for a halogen atom (fluorine,

chlorine, bromine, or iodine). Alkyl halides are

classified into primary, secondary, and tertiary

alkyl halides, according to the degree of

substitution of the particular carbon atom that

carries the halogen.

|

Primary, secondary, and tertiary alkyl

halides (X = F, Cl, Br, and I,

respectively). |

Vinyl halides are often classified as the fourth

type of alkyl halides.

|

Different degrees of abstraction in the

illustration of vinyl iodide's

structure. |

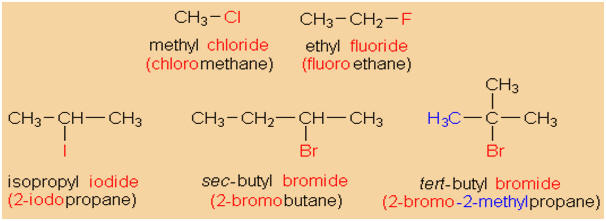

In the most generally accepted nomenclature of alkyl

halides the name of the alkyl residue is followed by

the halide's name, such as is the case with "methyl

iodide" and "ethyl chloride". In the IUPAC

nomenclature of alkyl halides (depicted in brackets

in the illustration below), an alkyl halide is

considered to be a substituted alkane. That is, the

name of the halogen is followed by the alkane's

name, such as, for example, "iodomethane" and

"chloromethane". If an alkyl halide contains more

than one halogen, the halogen names are noted in

alphabetical order, such as in

"1-chloro-2-iodobutane".

Examples of alkyl halide nomenclature.

Haloalkane style:

-

The root name is based on the longest chain containing

the halogen.

-

This root give the alkane part of the name.

-

The type of halogen defines the halo prefix, e.g.

chloro-

-

The chain is numbered so as to give the halogen the

lowest possible number

Alkyl halide style:

-

The root name is based on the longest chain containing

the halogen.

-

This root give the alkyl part of the name.

-

The type of halogen defines the halide suffix, e.g.

chloride

-

The chain is numbered so as to give the halogen the

lowest possible number.

|

Haloalkane style:

-

Functional group is an alkane, therefore

suffix = -ane

-

The longest continuous chain is C3 therefore

root = prop

-

The substituent is a chlorine, therefore

prefix = chloro

-

The first point of difference rule requires

numbering from the right as drawn,

the substituent locant is 1-

1-chloropropane

|

CH3CH2CH2Cl |

|

Alkyl halide style:

-

The alkyl group is C4, it's a tert-butyl

-

The halogen is a bromine, therefore suffix =

bromide

tert-butyl

bromide

Haloalkane style:

-

Functional group is an alkane, therefore

suffix = -ane

-

The longest continuous chain is C3 therefore

root = prop

-

The substituent is a bromine, therefore

prefix = bromo

-

There is a C1 substituent = methyl

-

The substituent locants are both 2-

2-bromo-2-methylpropane |

(CH3)3CBr |

|

Haloalkane style:

-

Functional group is an alkene, therefore

suffix = -ene

-

The longest continuous chain is C4 therefore

root = but

-

The substituent is a bromine, therefore

prefix = bromo

-

Since bromine is named as a substituent, the

alkene gets priority

-

The first point of difference rule requires

numbering from the left as drawn to

make the alkene group locant 1-

-

Therefore the bromine locant 4-

4-bromobut-1-ene |

CH2=CHCH2CH2Br |

Physical properties

The physical properties of alkyl halides differ considerably

from that of the corresponding alkanes. The strength and

length of the carbon-halogen bond and the dipole moments and

boling points of alkyl halides are determined by the bond's

polarity, as well as the size of the various halogen atoms:

�

The C-X bond strength decreases with an increase in the size

of the halogen (X), because the size of the halogen's p

orbital increases, as well. Thus, the p orbital becomes

hazier, and the overlap with the carbon's orbital

deteriorates. As a result, the C-X bond is weakend and

elongated.

Bond lenghts,

dipole moments, and dissociation energies of methyl halidies

( CH3X)

|

Methyl halide (halomethan) |

|

|

|

|

|

Bond length (pm) |

158.5 |

178.4 |

192.9 |

213.9 |

|

Dipole moment (D) |

1.85 |

1.87 |

1.81 |

1.62 |

|

Dissociation energy (kj/mol) |

416 |

356 |

297 |

239 |

�

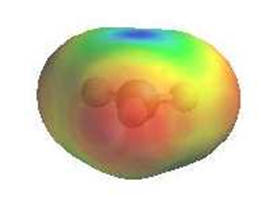

Halogens (F, Cl, and Br) are comparably more electronegative

than carbon is. Consequently, carbon atoms that carry

halogens are partially positively charged while the halogen

is partially negatively charged. The polarity of the C-X

bond causes a measureable dipole moment. As a result of the

partial positive charge, the carbon atom displays an

electrophilic character. The chemical behaviour of alkyl

halides is mainly determined by the carbon's

electrophilicity.

Polar character of a C-X bond

Dipole-dipole interaction in alky halides

�

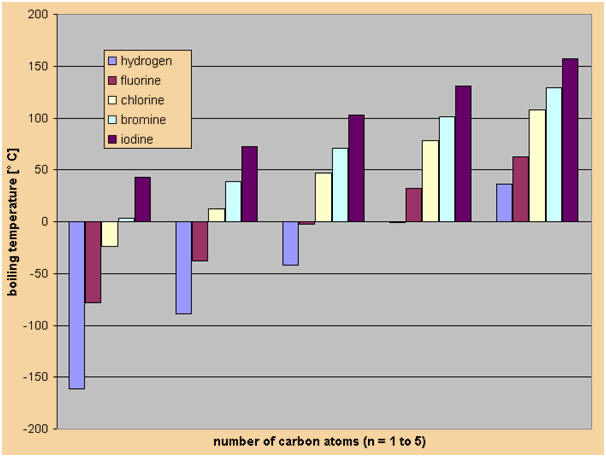

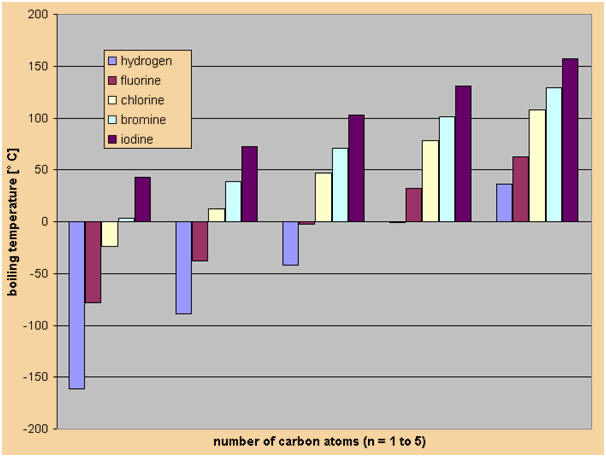

The boiling points of alkyl halides are considerably

higher than that of the corresponding alkanes. The main

reason for this is the dipole moment of alkyl halides,

which leads to attractive dipole-dipole interactions in

liquid alkyl halides. Furthermore, the higher molar mass

and the stronger London forces (Cl, Br, and I) lead to

higher boiling points. The main reason of the stronger

London forces between alkyl halides is the fact that the

electron shell of halogens is larger than that of

hydrogen and carbon. In larger electron shells, the

electrons are not as strongly attracted by the nucleus

as in small electron shells. Consequently, the

interactions between the electron shells of larger atoms

are stronge

Boiling points of alkanes (X = H) and alkyl halides (X =

F, Cl, Br, I) (in �C).

Structure:

-

The alkyl halide functional group consists of an sp3

hybridised C atom bonded to a halogen, X, via a σ

bond.

-

The carbon halogen bonds are typically quite polar

due to the electronegativity and polarisability of

the halogen.

Reactivity:

-

The halogens (Cl, Br and I) are good leaving groups.

-

The polarity makes the C atom electrophilic and

prone to attack by nucleophiles via

SN1 or

SN2 reactions.

-

Bases can remove β-hydrogens and cause

1,2-elimination to form alkenes via E1 or E2

reactions.

-

Insertion of a metal (esp. Mg) creates an

organometalic species.

Preparation

Alkyl halides may be synthesized by

addition, as well as by

substitution reactions:

�

Addition of a hydrogen halide HX ( HX= HCl,

HBr or HI)

to an alkene yields the corresponding monohalogenated alkene

(Markovnikv addition). The addition of bromine and chlorine

to alkenes results in the corresponding vicinal alykl

dihalides.

|

Electrophilic

addition of hydrogen halides and halogens to

1-methylcyclopentene. |

|

|

�

The

radical substitution of an alkane's hydrogen with

bromine or chlorine is yet another method of synthesizing

alkyl halides. However, the praticality of this method is

limited, as mixtures of alkyl halides with varying degree of

halogenation are obtained.

E HALOGENATION REACTION

-

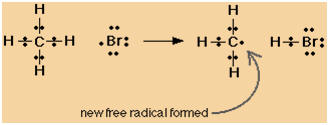

A very simple example of the halogenation of alkanes is

the chlorination of methane, as shown in the

illustration below. The products are HCl and

chloromethane.

-

The REACTION TYPE is SUBSTITUTION, since a

hydrogen of methane is replaced by a chlorine atom. The

MECHANISTIC TYPE, as we will see, is Homolytic

or Radical. The overall designation of the reaction,

then, is SH (S WITH A SUBSCRIPT H).

-

Virtually any C-H bond in which the carbon atom is

tetrahedrally hybridized can be chlorinated, so that

chloromethane can be further converted to

dichloromethane, and this on to trichloromethane

(chloroform), and finally to tetrachloromethane (carbon

tetrachloride). You may recognize these chlorinated

compounds as common solvents, both in the laboratory and

in commercial uses.

-

In the chlorination of alkanes more complex than methane

or ethane, more than one monochloroalkane can be formed.

We will refer to the preference for the formation of one

constitutional isomer over the other as regiospecificity.

For example, propane can be converted to both

1-chloropropane and 2-chloropropane. Actually, both are

formed, but the 2-chloropropane is slightly, but only

slightly, preferred. Thus, the reaction is not very

stereooregiospecific.

|

Radical chlorination of methane. |

|

|

Mechanism

|

Simplifying all this for exam purposes:

Initiation Step:

|

1- |

Br2��>2Br |

Propagation Step:

|

2- |

CH4 + Br ��>CH3 ��>CH3 + HBr

+ HBr |

|

3- |

CH3 + Br2��>CH3Br

+ Br

+ Br2��>CH3Br

+ Br |

Termination Step:

|

4- 2Br ��>Br2 ��>Br2

|

|

5- |

CH3 + Br

+ Br ��>CH3Br ��>CH3Br

|

|

6- |

CH3 + CH3

+ CH3 ��>CH3CH3 ��>CH3CH3

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

Br2��>2Br |

| |

Br + Br-Br��>Br-Br

+ Br

+ Br-Br��>Br-Br

+ Br

|

|

| |

|

| |

CH4 + Br ��>CH3 ��>CH3 + HBr

+ HBr |

.

| |

CH3 + Br

+ Br ��>CH3Br ��>CH3Br

|

| |

CH3 + CH3

+ CH3 ��>CH3CH3 ��>CH3CH3

|

| |

CH3 + Br2��>CH3Br

+ Br

+ Br2��>CH3Br

+ Br |

|

|

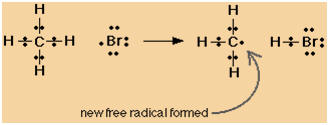

-

This is our first example of a reaction mechanism in

which radicals are involved. The definition of a

radical is any species which has an unpaired or odd

electron. There are two radical species involved

in this mechanism, the chlorine atom and the methyl

radical. The naming of organic radicals is

simple, it is essentially the name of the

corresponding substituent with the name radical

being appended to it.

-

The overall reaction is said to be a homolytic

substitution reaction, as noted previously,

because the bonds which are broken are broken

homolytically, i.e., one electron departing with

each component of the bond. In homolytic cleavages

radicals are always formed, so the reaction

mechanism can also be called radical substitution.

-

One specific way in which radical reactions can

occur is by means of a radical chain reaction.

It is important to keep in mind that not all

radical reaction mechanisms are radical chain

mechanisms. A radical chain mechanism is one in

which a particular set or two or three steps is

repeated over and over without the necessity of

generating more radicals. This is seen in steps 2

and 3 of the mechanism above. The stage of the

reaction which represents the chain is called the

propagation cycle. It is so called because in

it, the observed products (HCl and chloromethane)

are propagated or made. An efficient set of

progpagation reactions is essential to a successful

radical chain mechanism.

-

Overall, this or any, radical chain mechanism

consists of three discrete stages or parts.

The first part is called initiation. In the

initiation stage of the mechanism (step 1), the

radicals which are necessary to enter the

propagation cycle are generated. This typically

involves the homolytic cleavage of a covalent bond,

and so it requires energy. In this case, it is the

Cl-Cl bond which is cleavaged homolytically.It is

for this reason that the chlorination reaction

requires the input of either heat or photochemical

energy.

-

As noted above, the second stage or part of the

radical chain mechanism is the propagation cycle.

An efficient propagation cycle uses a relatively

few radicals to generate a large amount of product.

It is desirable that for each radical produced in

the initiation reaction, hundreds or even thousands

of product molecules be generated before the radical

is destroyed.

-

The third and final stage of the radical chain

mechanism is termination. Termination is the

undesirable but unavoidable coupling between two

radicals which destroys the chain carrying radicals

and stops the current radical chain. It is thus the

competitor of propagation. Because of this

continuing consumption of radicals, initiation must

continue to progressively generate more radicals.

For a chain reaction to be effective, propagation by

the radicals must be much more efficient than

coupling between them.These coupling reactions are

extrememly fast, because no bond is broken and one

bond is formed. However, since the radical

concentrations are extremely small, the probability

of one radical meeting another is much less than for

a radical to meet a molecule of chlorine or methane.

�

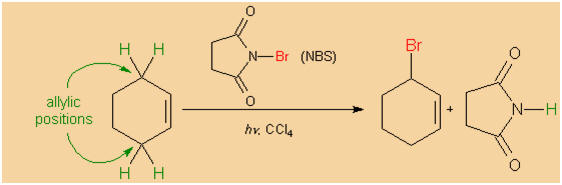

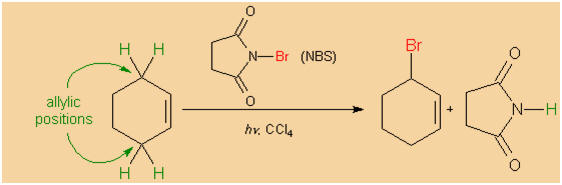

Nevertheless, a selective monohalogenation in allylic

position may be achieved by applying N-bromosuccinimide (NBS).

This method was introduced by Karl Ziegler in 1942.

|

Bromination of cyclohexene in allylic position. |

|

|

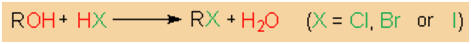

�

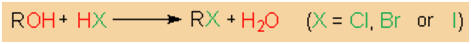

A standard method of synthesizing alkyl halides is the

treatment of alcohols with HCl, HBr or BI.

The reaction is a nucleophilic substitution in which the

alcohol's hydroxy group is exchanged for the halide ion.

Hydroxide is a poor leaving group though it may be converted

into the good leaving group water through protonation by a

hydrogen halide. However, at moderate temperature, the

reaction is practicable only with tertiary alcohols. A

higher reaction temperature is required if the reaction

ought to be carried out with primary or secondary alcohols.

Otherwise, the reaction rate will be too low. In contrast,

the reaction of tertiary alcohols with hydrogen halides is

much more rapid. As a result, considerable conversion is

obtained within a period of only a few minutes when pure

HCl, or HBr is passed through the alcohol. However, the

hydrogen halides in alkyl halides' syntheses are more

frequently generated in situ by treating the halide ion with

phosphoric or sulfuric acid.

|

Alkyl halide synthesis by treatment of alcohols

with HX. |

|

|

|

Chlorination of 1-methylcyclohexanol. |

|

|

HBr and HI are usually used for the synthesis of alkyl

bromides and iodides, respectively. However, PBr3 may

also be applied. Aside from HCl, inorganic acid halides,

such as thionyl chloride (SOCl2),

phosphorus trichloride (PCl3),

phosphorus pentachloride (PCl5),

or phosphorus oxychloride (POCl3),

are common chlorinating agents in alkyl chlorides'

syntheses. If such chlorination agents are employed in the

conversion of alcohols into alkyl halides, rearrangements

are much less often the case than with HCl.

|

Halogenation of secondary alcohols by inorganic

acid halides. |

|

|

|

|

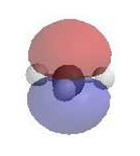

Reaction of

Alkyl Halides

The functional group of alkyl halides is a carbon-halogen bond, the

common halogens being fluorine, chlorine, bromine and iodine. With the

exception of iodine, these halogens have electronegativities

significantly greater than carbon. Consequently, this functional group

is polarized so that the carbon is electrophilic and the halogen is

nucleophilic, as shown in the drawing on the right. Two characteristics

other than electronegativity also have an important influence on the

chemical behavior of these compounds. The first of these is covalent

bond strength. The strongest of the carbon-halogen covalent bonds is

that to fluorine. Remarkably, this is the strongest common single bond

to carbon, being roughly 30 kcal/mole stronger than a carbon-carbon bond

and about 15 kcal/mole stronger than a carbon-hydrogen bond. Because of

this, alkyl fluorides and fluorocarbons in general are chemically and

thermodynamically quite stable, and do not share any of the

reactivity patterns shown by the other alkyl halides. The

carbon-chlorine covalent bond is slightly weaker than a carbon-carbon

bond, and the bonds to the other halogens are weaker still, the bond to

iodine being about 33% weaker. The second factor to be considered is the

relative stability of the corresponding halide anions, which is

likely the form in which these electronegative atoms will be replaced.

This stability may be estimated from the relative acidities of the H-X

acids, assuming that the strongest acid releases the most stable

conjugate base (halide anion). With the exception of HF (pKa

= 3.2), all the hydrohalic acids are very strong, small differences

being in the direction HCl < HBr < HI.

Reactions at

sp�-hybridized

Carbons: Substitution and Elimination

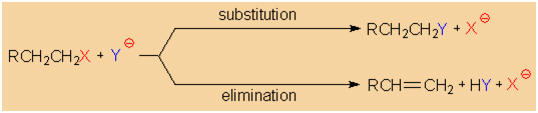

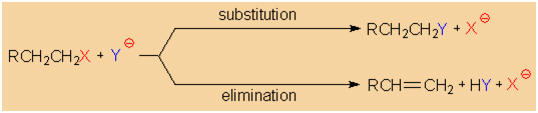

Fundamentally, organic compounds that contain a carbon with a more

electronegative substituent display two types of reaction: nucleophilic

substitution reactions and elimination reactions. In nucleophilic

substitution, the electronegative substituent (leaving group) is

exchanged (substituted) for another substitutent (nucleophile). In

elimination however, the electronegative substituent is released from

the organic molecule along with another atom or group, which is usually

a hydrogen from the vicinal carbon.

Alkyl halides (R-X) are characteristic examples of such organic compounds. The

leaving groups in nucleophilic substitutions and eliminations with alkyl halides

are the halide anions ((Xˉ)

Cl ˉ,

Br ˉ,

I ˉand

F ˉ.

virtually never functions as a leaving group.

|

Reaction types of alkyl halides. |

|

|

Substitution reactions are particularly useful in organic chemistry - though

this is not only because they enable the synthetically easily available alkyl

halides to be converted into multiple other organic compounds.

Substitution and Elimination

The characteristics noted above lead us to anticipate certain types of

reactions that are likely to occur with alkyl halides. In describing

these, it is useful to designate the halogen-bearing carbon as alpha

and the carbon atom(s) adjacent to it as beta, as noted in the

first four equations shown below. Replacement or substitution of the

halogen on the α-carbon (colored maroon) by a nucleophilic reagent is a

commonly observed reaction, as shown in equations

1, 2, 5, 6 & 7

below. Also, since the electrophilic character introduced by the halogen

extends to the β-carbons, and since nucleophiles are also bases, the

possibility of base induced H-X elimination must also be considered, as

illustrated by equation

3.

Finally, there are some combinations of alkyl halides and nucleophiles

that fail to show any reaction over a 24 hour period, such as the

example in equation

4.

For consistency, alkyl bromides have been used in these examples.

Similar reactions occur when alkyl chlorides or iodides are used, but

the speed of the reactions and the exact distribution of products will

change.

In order to understand why some combinations of alkyl halides and

nucleophiles give a substitution reaction, whereas other combinations

give elimination, and still others give no observable reaction, we must

investigate systematically the way in which changes in reaction

variables perturb the course of the reaction. The following general

equation summarizes the factors that will be important in such an

investigation.

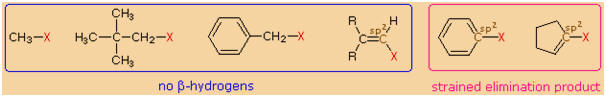

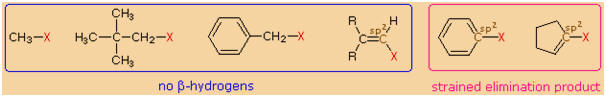

One conclusion, relating the structure of the R-group to possible

products, should be immediately obvious. If R- has no beta-hydrogens

an elimination reaction is not possible, unless a structural

rearrangement occurs first. The first four halides shown on the left

below do not give elimination reactions on treatment with base, because

they have no β-hydrogens. The two halides on the right do not normally

undergo such reactions because the potential elimination products have

highly strained double or triple bonds.

It is also worth noting that sp2

hybridized C�X compounds, such as the three on the right, do not

normally undergo nucleophilic substitution reactions, unless other

functional groups perturb the double bond(s).

Using the general reaction shown above as our reference, we can identify

the following variables and observables.

|

Variables |

R

change α-carbon from 1� to 2� to 3�

if the α-carbon is a chiral center, set as (R) or

(S)

X

change from Cl to Br to I (F is relatively unreactive)

Nu:

change from anion to neutral; change basicity; change

polarizability

Solvent

polar vs. non-polar; protic vs. non-protic |

|

Observables |

Products

substitution, elimination, no reaction.

Stereospecificity if the α-carbon is a chiral

center what happens to its configuration?

Reaction Rate measure as a function of reactant

concentration. |

When several reaction variables may be changed, it is important to

isolate the effects of each during the course of study. In other words:

only one variable should be changed at a time, the others being

held as constant as possible. For example, we can examine the effect of

changing the halogen substituent from Cl to Br to I, using ethyl as a

common R�group, cyanide anion as a common nucleophile, and ethanol as a

common solvent. We would find a common substitution product, C2H5�CN,

in all cases, but the speed or rate of the reaction would increase in

the order: Cl < Br < I. This reactivity order reflects both the strength

of the C�X bond, and the stability of X(�)

as a leaving group, and leads to the general conclusion that alkyl

iodides are the most reactive members of this functional class.

1. Nucleophilicity

Recall the definitions of electrophile and nucleophile:

Electrophile:

An electron deficient atom, ion or molecule that has an affinity for

an electron pair, and will bond to a base or nucleophile.

Nucleophile:

An atom, ion or molecule that has an electron pair that may be donated

in forming a covalent bond to an electrophile (or Lewis acid).

If we use a common alkyl halide, such as methyl bromide, and a common

solvent, ethanol, we can examine the rate at which various nucleophiles

substitute the methyl carbon. Nucleophilicity is thereby related

to the relative rate of substitution reactions at the halogen-bearing

carbon atom of the reference alkyl halide. The most reactive

nucleophiles are said to be more nucleophilic than less reactive members

of the group. The nucleophilicities of some common Nu:(�)

reactants vary as shown in the following chart.

Nucleophilicity:

CH3CO2(�)

< Cl(�)

< Br(�)

< N3(�)

< CH3O(�)

< CN(�)

< I(�)

< SCN(�)

< I(�)

< CH3S(�)

The reactivity range encompassed by these reagents is over 5,000 fold,

thiolate being the most reactive. Note that by using methyl bromide as

the reference substrate, the complication of competing elimination

reactions is avoided. The nucleophiles used in this study were all

anions, but this is not a necessary requirement for these substitution

reactions. Indeed reactions

6 & 7,

presented at the beginning of this section, are examples of neutral

nucleophiles participating in substitution reactions. The cumulative

results of studies of this kind has led to useful empirical rules

pertaining to nucleophilicity:

(i)

For a given element, negatively charged species are more nucleophilic

(and basic) than are equivalent neutral species.

(ii) For a given period of the periodic table, nucleophilicity

(and basicity) decreases on moving from left to right.

(iii) For a given group of the periodic table, nucleophilicity

increases from top to bottom (i.e. with increasing size),

although there is a solvent dependence due to hydrogen bonding. Basicity

varies in the opposite manner.

2. Solvent Effects

Solvation

of nucleophilic anions markedly influences their reactivity. The

nucleophilicities cited above were obtained from reactions in methanol

solution. Polar, protic solvents such as water and alcohols solvate

anions by hydrogen bonding interactions, as shown in the diagram on the

right. These solvated species are more stable and less reactive than the

unsolvated "naked" anions. Polar, aprotic solvents such as DMSO

(dimethyl sulfoxide), DMF (dimethylformamide) and acetonitrile do not

solvate anions nearly as well as methanol, but provide good solvation of

the accompanying cations. Consequently, most of the nucleophiles

discussed here react more rapidly in solutions prepared from these

solvents. These solvent effects are more pronounced for small basic

anions than for large weakly basic anions. Thus, for reaction in DMSO

solution we observe the following reactivity order:

Nucleophilicity:

I(�)

< SCN(�)

< Br(�)

< Cl(�)

≈ N3(�)

< CH3CO2

(�)

< CN(�)

≈ CH3S(�)

< CH3O(�)

Note that this order is roughly the order of increasing basicity.

3. The Alkyl Moiety

Some of the most important information concerning nucleophilic

substitution and elimination reactions of alkyl halides has come from

studies in which the structure of the alkyl group has been varied. If we

examine a series of alkyl bromide substitution reactions with the strong

nucleophile thiocyanide (SCN) in ethanol solvent, we find large

decreases in the rates of reaction as alkyl substitution of the

alpha-carbon increases. Methyl bromide reacts 20 to 30 times faster than

simple 1�-alkyl bromides, which in turn react about 20 times faster than

simple 2�-alkyl bromides, and 3�-alkyl bromides are essentially

unreactive or undergo elimination reactions. Furthermore, β-alkyl

substitution also decreases the rate of substitution, as witnessed by

the failure of neopentyl bromide, (CH3)3CCH2-Br

(a 1�-bromide), to react.

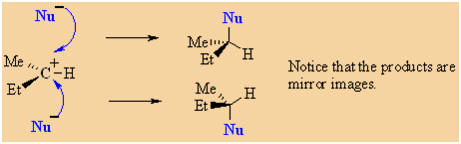

Alkyl halides in which the alpha-carbon is a chiral center provide

additional information about these nucleophilic substitution reactions.

Returning to the examples presented at the beginning of this section, we

find that reactions

2, 5 & 6

demonstrate an inversion of configuration when the cyanide nucleophile

replaces the bromine. Other investigations have shown this to be

generally true for reactions carried out in non-polar organic solvents,

the reaction of (S)-2-iodobutane with sodium azide in ethanol being just

one example ( in the following equation the alpha-carbon is maroon and

the azide nucleophile is blue). Inversion of configuration during

nucleophilic substitution has also been confirmed for chiral 1�-halides

of the type RCDH-X,

where the chirality is due to isotopic substitution.

(S)-CH3CHICH2CH3

+ NaN3

��>

(R)-CH3CHN3CH2CH3

+ NaI

We can now piece together a plausible picture of how nucleophilic

substitution reactions of 1� and 2�-alkyl halides take place. The

nucleophile must approach the electrophilic alpha-carbon atom from the

side opposite the halogen. As a covalent bond begins to form between the

nucleophile and the carbon, the carbon halogen bond weakens and

stretches, the halogen atom eventually leaving as an anion. The diagram

on the right shows this process for an anionic nucleophile. We call this

description the SN2

mechanism, where S stands for Substitution, N

stands for Nucleophilic and 2 stands for bimolecular

(defined below). In the SN2

transition state the alpha-carbon is hybridized sp2 with

the partial bonds to the nucleophile and the halogen having largely

p-character. Both the nucleophile and the halogen bear a partial

negative charge, the full charge being transferred to the halogen in the

products. The consequence of rear-side bonding by the nucleophile is an

inversion of configuration about the alpha-carbon. Neutral nucleophiles

react by a similar mechanism, but the charge distribution in the

transition state is very different.

This mechanistic model explains many aspects of the reaction. First, it

accounts for the fact that different nucleophilic reagents react at very

different rates, even with the same alkyl halide. Since the transition

state has a partial bond from the alpha-carbon to the nucleophile,

variations in these bond strengths will clearly affect the activation

energy, ΔE�,

of the reaction and therefore its rate. Second, the rear-side approach

of the nucleophile to the alpha-carbon will be subject to hindrance by

neighboring alkyl substituents, both on the alpha and the beta-carbons.

The following models clearly show this "steric hindrance" effect.

The two models displayed below start as methyl bromide, on the left,

and ethyl bromide, on the right. These may be replaced by

isopropyl, tert-butyl, neopentyl, and benzyl bromide models by pressing

the appropriate buttons. (note that when first activated, this display

may require clicking twice on the selected button.) In each picture the

nucleophile is designated by a large deep violet sphere, located 3.75

Angstroms from the alpha-carbon atom (colored a dark gray), and located

exactly opposite to the bromine (colored red-brown). This represents a

point on the trajectory the nucleophile must follow if it is to bond to

the back-side of the carbon atom, displacing bromide anion from the

front face. With the exception of methyl and benzyl, the other alkyl

groups present a steric hindrance to the back-side approach of the

nucleophile, which increases with substitution alpha and beta to the

bromine. The hydrogen (and carbon) atoms that hinder the nucleophile's

approach are colored a light red. The magnitude of this steric hindrance

may be seen by moving the models about in the usual way, and is clearly

greatest for tert-butyl and neopentyl, the two compounds that fail to

give substitution reactions.

4. Molecularity

If a chemical reaction proceeds by more than one step or stage, its

overall velocity or rate is limited by the slowest step, the

rate-determining step. This "bottleneck concept" has analogies in

everyday life. For example, if a crowd is leaving a theater through a

single exit door, the time it takes to empty the building is a function

of the number of people who can move through the door per second. Once a

group gathers at the door, the speed at which other people leave their

seats and move along the aisles has no influence on the overall exit

rate. When we describe the mechanism of a chemical reaction, it is

important to identify the rate-determining step and to determine its "molecularity".

The molecularity of a reaction is defined as the number of

molecules or ions that participate in the rate determinining step. A

mechanism in which two reacting species combine in the transition state

of the rate-determining step is called bimolecular. If a single

species makes up the transition state, the reaction would be called

unimolecular. The relatively improbable case of three independent

species coming together in the transition state would be called

termolecular.

5. Kinetics

One way of investigating the molecularity of a given reaction is to

measure changes in the rate at which products are formed or reactants

are lost, as reactant concentrations are varied in a systematic fashion.

This sort of study is called

kinetics,

and the goal is to write an equation that correlates the observed

results. Such an equation is termed a kinetic expression, and for a

reaction of the type: A + B ���> C + D it takes the form: Reaction

Rate = k[A]

n[B]

m,

where the rate constant k is a proportionality constant that

reflects the nature of the reaction, [A] is the concentration of

reactant A, [B] is the concentration of reactant B, and n

& m are exponential numbers used to fit the rate equation to the

experimental data. Chemists refer to the sum n + m as the kinetic

order of a reaction. In a simple bimolecular reaction n & m would

both be 1, and the reaction would be termed second order,

supporting a mechanism in which a molecule of reactant A and one of B

are incorporated in the transition state of the rate-determining step. A

bimolecular reaction in which two molecules of reactant A (and no B) are

present in the transition state would be expected to give a kinetic

equation in which n=2 and m=0 (also second order). The kinetic

expressions found for the reactions shown at the beginning of this

section are written in blue in the following equations. Each different

reaction has its own distinct rate constant, k#.

All the reactions save

7

display second order kinetics, reaction

7

is first order.

It should be recognized and remembered that the molecularity of a

reaction is a theoretical term referring to a specific mechanism. On the

other hand, the kinetic order of a reaction is an experimentally derived

number. In ideal situations these two should be the same, and in most of

the above reactions this is so. Reaction

7

above is clearly different from the other cases reported here. It not

only shows first order kinetics (only the alkyl halide concentration

influences the rate), but the chiral 3�-alkyl bromide reactant undergoes

substitution by the modest nucleophile water with extensive racemization.

Note that the acetonitrile cosolvent does not function as a nucleophile.

It serves only to provide a homogeneous solution, since the alkyl halide

is relatively insoluble in pure water.

One of the challenges faced by early workers in this field was to

explain these and other differences in a rational manner.

Two discrete mechanisms for nucleophilic substitution reactions will be

described in the next section.

Reactions of Alkyl Halides with

Reducing Metals

The alkali metals (Li, Na, K etc.) and the alkaline earth metals

(Mg and Ca, together with Zn) are good reducing agents, the former being

stronger than the latter. Sodium, for example, reduces elemental

chlorine to chloride anion (sodium is oxidized to its cation), as do the

other metals under varying conditions. In a similar fashion these same

metals reduce the carbon-halogen bonds of alkyl halides. The halogen is

converted to halide anion, and the carbon bonds to the metal (the carbon

has carbanionic character). Halide reactivity increases in the order: Cl

< Br < I. The following equations illustrate these reactions for the

commonly used metals lithium and magnesium (R may be hydrogen or alkyl

groups in any combination). The alkyl magnesium halides described in the

second reaction are called Grignard Reagents after the French

chemist who discovered them. The other metals mentioned above react in a

similar manner, but the two shown here are the most widely used.

Although the formulas drawn here for the alkyl lithium and Grignard

reagents reflect the stoichiometry of the reactions and are widely used

in the chemical literature, they do not accurately depict the structural

nature of these remarkable substances. Mixtures of polymeric and other

associated and complexed species are in equilibrium under the conditions

normally used for their preparation.

|

R3C-X

+ 2Li

��>

R3C-Li +

LiX

An Alkyl Lithium Reagent

R3C-X +

Mg

��>

R3C-MgX A Grignard Reagent |

The metals referred to here are insoluble in most organic solvents,

hence these reactions are clearly heterogeneous, i.e. take place on the

metal surface. The conditions necessary to achieve a successful reaction

are critical.

First, the metal must be clean and finely divided so as to

provide the largest possible surface area for reaction.

Second, a suitable solvent must be used. For alkyl lithium

formation pentane, hexane or ethyl ether may be used; but ethyl ether or

THF are essential for Grignard reagent formation.

Third, since these organometallic compounds are very reactive,

contaminants such as water, alcohols and oxygen must be avoided.

These reactions are obviously substitution reactions, but they

cannot be classified as nucleophilic substitutions, as were the earlier

reactions of alkyl halides. Because the functional carbon atom has been

reduced, the polarity of the resulting functional group is inverted (an

originally electrophilic carbon becomes nucleophilic). This change,

shown below, makes alkyl lithium and Grignard reagents unique and useful

reactants in synthesis.

Reactions of organolithium and Grignard reagents reflect the

nucleophilic (and basic) character of the functional carbon in these

compounds. Many examples of such reactions will be encountered in future

discussions, and five simple examples are shown below. The first and

third equations demonstrate the strongly basic nature of these

compounds, which bond rapidly to the weakly acidic protons of water and

methyl alcohol (colored blue). The nucleophilic carbon of these reagents

also bonds readily with electrophiles such as iodine (second equation)

and carbon dioxide (fifth equation). The polarity of the carbon-oxygen

double bonds of CO2

makes the carbon atom electrophilic, shown by the formula in the shaded

box, so the nucleophilic carbon of the Grignard reagent bonds to this

site. As noted above, solutions of these reagents must also be protected

from oxygen, since peroxides are formed (equation 4).

Another important reaction exhibited by these organometallic reagents is

metal exchange. In the first example below, methyl lithium reacts

with cuprous iodide to give a lithium dimethylcopper reagent, which is

referred to as a Gilman reagent. Other alkyl lithiums give

similar Gilman reagents. A useful application of these reagents is their

ability to couple with alkyl, vinyl and aryl iodides, as shown in the

second equation. Later we shall find that Gilman reagents also display

useful carbon-carbon bond forming reactions with conjugated enones and

with acyl chlorides.

|

2 CH3Li

+ CuI

��> (CH3)2CuLi + LiI

Formation of a Gilman Reagent

(C3H7)2CuLi + C6H5I

��>

C6H5-C3H7

+ LiI + C3H7Cu A

Coupling Reaction |

The formation of organometallic reagents from alkyl halides is more

tolerant of structural variation than were the nucleophilic

substitutions described earlier. Changes in carbon hybridization have little effect on the

reaction, and 1�, 2� and 3�-alkyl halides all react in the same manner.

One restriction, of course, is the necessary absence of incompatible

functional groups elsewhere in the reactant molecule. For example,

5-bromo-1-pentanol fails to give a Grignard reagent (or a lithium

reagent) because the hydroxyl group protonates this reactive function as

soon as it is formed.

BrCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2OH

+

Mg

��>

[

BrMgCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2OH

]

��>

HCH2CH2CH2CH2CH2OMgBr

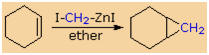

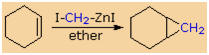

Reactions of Dihalides

If two halogen atoms are present in a given compound, reactions

with reducing metals may take different paths depending on how close the

carbon-halogen bonds are to each other. If they are separated by four or

more carbons, as in the first example below, a bis-organometallic

compound may be formed. However, if the halogens are bonded to adjacent

(vicinal)

carbons, an elimination takes place with formation of a double bond.

Since vicinal-dihalides are usually made by adding a halogen to a double

bond, this reaction is mainly useful for relating structures to each

other. The last example, in which two halogens are bonded to the same

carbon, referred to as geminal (twinned), gives an unusual

reagent which may either react as a carbon nucleophile or, by

elimination, as a

carbene. Such reagents are often termed carbenoid.

The solution structure of the Simmons-Smith reagent is less well

understood than that of the Grignard reagent, but the formula given here

is as useful as any that have been proposed. Other alpha-halogenated

organometallic reagents, such as ClCH2Li,

BrCH2Li,

Cl2CHLi

and Cl3CLi,

have been prepared, but they are substantially less stable and must be

maintained at very low temperature (ca. -100 � C) to avoid loss of LiX.

The stability and usefulness of the Simmons-Smith reagent may be

attributed in part to the higher covalency of the carbon-zinc bond

together with solvation and internal coordination of the zinc.

Hydrolysis (reaction with water) gives methyl iodide, confirming the

basicity of the carbon; and reaction with alkenes gives cyclopropane

derivatives, demonstrating the carbene-like nature of the reagent. The

latter transformation is illustrated by the equation on the right.

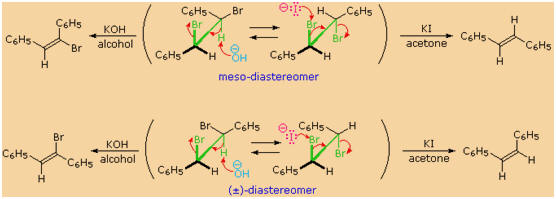

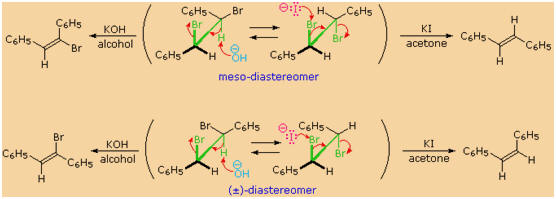

Elimination reactions of the stereoisomeric

1,2-dibromo-1,2-diphenylethanes provide a nice summary of the principles

discussed above. The following illustration shows first the meso-diastereomer

and below it one enantiomer of the racemic-diastereomer. In each case

two conformers are drawn within parentheses, and the anti-relationship

of selected vicinal groups in each is colored green. The reaction

proceeding to the left is a dehydrohalogenation induced by treatment

with KOH in alcohol. Since this is a

stereospecific elimination, each diastereomer gives a

different stereoisomeric product. The reaction to the right is a

dehalogenation (the reverse of halogen addition to an alkene), caused by

treatment with iodide anion. Zinc dust effects the same reaction, but

with a lower degree of stereospecificity. The mechanism of the iodide

anion reaction is shown by red arrows in the top example. A similar

mechanism explains the comparable elimination of the racemic isomer. In

both reactions an anti-transition state is observed.

The two stereoisomers of 1-bromo-1,2-diphenylethene (shown on the

left of the diagram) undergo a second dehydrobromination reaction on

more vigorous treatment with base, as shown in the following equation.

This elimination generates the same alkyne (carbon-carbon triple bond)

from each of the bromo-alkenes. Interestingly, the (Z)-isomer (lower

structure) eliminates more rapidly than the (E)-isomer (upper

structure), again showing a preference for anti-orientation of

eliminating groups.

C6H5CH=CBrC6H5

+ KOH

��>

C6H5C≡CC6H5

+ KBr + H2O

Preparation of Alkynes by

Dehydrohalogenation

The last reaction shown above suggests that alkynes might be

prepared from alkenes by a two stage procedure, consisting first of

chlorine or bromine addition to the double bond, and secondly a base

induced double dehydrohalogenation. For example, reaction of 1-butene

with bromine would give 1,2-dibromobutane, and on treatment with base

this vicinal dibromide would be expected to yield 1-bromo-1-butene

followed by a second elimination to 1-butyne.

CH3CH2CH=CH2

+

Br2

��>

CH3CH2CHBr�CH2Br

+ base

��>

CH3CH2CH=CHBr

+ base

��>

CH3CH2C≡CH

In practice this strategy works, but it requires care in the

selection of the base and solvent. If KOH in alcohol is used, the first

elimination is much faster than the second, so the bromoalkene may be

isolated if desired. Under more extreme conditions the second

elimination takes place, but isomerization of the triple bond also

occurs, with the more stable isomer (2-butyne) being formed along with

1-butyne, even becoming the chief product. To facilitate the second

elimination and avoid isomerization the very strong base sodium amide,

NaNH2,

may be used. Since ammonia is a much weaker acid than water (by a factor

of 1018),

its conjugate base is proportionally stronger than hydroxide anion (the

conjugate base of water), and the elimination of HBr from the

bromoalkene may be conducted at relatively low temperature. Also, the

acidity of the sp-hybridized C-H bond of the terminal alkyne traps the

initially formed 1-butyne in the form of its sodium salt.

CH3CH2C≡CH

+ NaNH2

��>

CH3CH2C≡C:(�)

Na(+)

+ NH3

An additional complication of this procedure is that the

1-bromo-1-butene product of the first elimination (see previous

equations) is accompanied by its 2-bromo-1-butene isomer, CH3CH2CBr=CH2,

and elimination of HBr from this bromoalkene not only gives 1-butyne

(base attack at C-1) but also 1,2-butadiene, CH3CH=C=CH2,

by base attack at C-3. Dienes of this kind, in which the central carbon

is sp-hybridized, are called allenes and are said to have

cumulated double bonds. They are usually less stable than their

alkyne isomers.

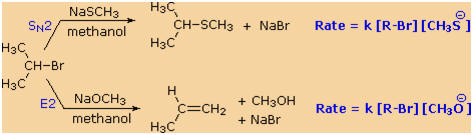

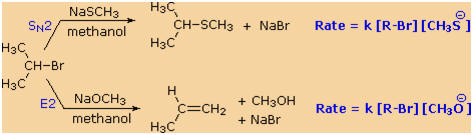

Elimination Reactions

1. The E2 Reaction

We

have not yet considered the factors that influence elimination

reactions, such as example

3 in the group presented at the

beginning of this section.

(3)

(CH3)3C-Br

+ CN(�)

��>

(CH3)2C=CH2

+

Br(�)

+ HCN

We know that t-butyl bromide is not expected to react by a SN2

mechanism. Furthermore, the ethanol solvent is not sufficiently polar to

facilitate a SN1

reaction. The other reactant, cyanide anion, is a good nucleophile; and

it is also a decent base, being about ten times weaker than bicarbonate.

Consequently, a base-induced elimination seems to be the only plausible

reaction remaining for this combination of reactants. To get a clearer

picture of the interplay of these factors consider the reaction of a

2�-alkyl halide, isopropyl bromide, with two different nucleophiles.

In the methanol solvent used here, methanethiolate has greater

nucleophilicity than methoxide by a factor of 100. Methoxide, on the

other hand is roughly 106

times more basic than methanethiolate. As a result, we see a clearcut

difference in the reaction products, which reflects nucleophilicity

(bonding to an electrophilic carbon) versus basicity (bonding to

a proton). Kinetic studies of these reactions show that they are both

second order (first order in R�Br and first order in Nu:(�)),

suggesting a bimolecular mechanism for each. The substitution reaction

is clearly SN2.

The corresponding designation for the elimination reaction is E2.

An energy diagram for the single-step bimolecular E2 mechanism is shown

on the right. We should be aware that the E2 transition state is less

well defined than is that of SN2 reactions. More bonds are being broken and formed, with the

possibility of a continuum of states in which the extent of C�H and C�X

bond-breaking and C=C bond-making varies. For example, if the R�groups

on the beta-carbon enhance the acidity of that hydrogen, then

substantial breaking of C�H may occur before the other bonds begin to be

affected. Similarly, groups that favor ionization of the halogen may

generate a transition state with substantial positive charge on the

alpha-carbon and only a small degree of C�H breaking. For most simple

alkyl halides, however, it is proper to envision a balanced transition

state, in which there has been an equal and synchronous change in all

the bonds. Such a model helps to explain an important regioselectivity

displayed by these elimination reactions.

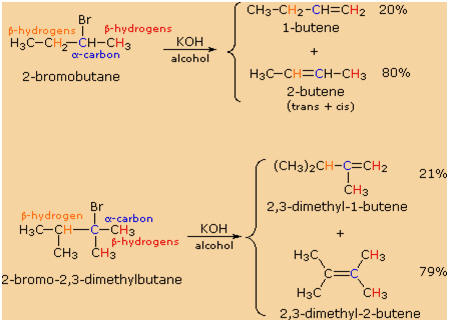

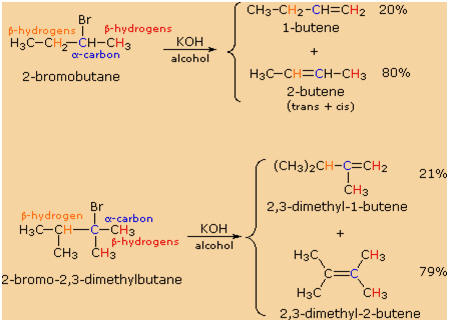

If two or more structurally distinct groups of beta-hydrogens are

present in a given reactant, then several constitutionally isomeric

alkenes may be formed by an E2 elimination. This situation is

illustrated by the 2-bromobutane and 2-bromo-2,3-dimethylbutane

elimination examples given below.

By using the strongly basic hydroxide nucleophile, we direct these

reactions toward elimination. In both cases there are two different sets

of beta-hydrogens available to the elimination reaction (these are

colored red and orange and the alpha carbon is blue). If the rate of

each possible elimination was the same, we might expect the amounts of

the isomeric elimination products to reflect the number of hydrogens

that could participate in that reaction. For example, since there are

three 1�-hydrogens (red) and two 2�-hydrogens (orange) on beta-carbons

in 2-bromobutane, statistics would suggest a 3:2 ratio of 1-butene and

2-butene in the products. This is not observed, and the latter

predominates by 4:1. This departure from statistical expectation is even

more pronounced in the second example, where there are six

1�-beta-hydrogens compared with one 3�-hydrogen. These results point to

a strong regioselectivity favoring the more highly substituted product

double bond, an empirical statement generally called the Zaitsev Rule.

The main factor contributing to Zaitsev Rule behavior is the

stability of the alkene. We noted earlier that carbon-carbon double

bonds are stabilized (thermodynamically) by alkyl substituents, and that

this stabilization could be evaluated by appropriate

heat of hydrogenation measurements. Since the E2 transition

state has significant carbon-carbon double bond character, alkene

stability differences will be reflected in the transition states of

elimination reactions, and therefore in the activation energy of the

rate-determining steps. From this consideration we anticipate that if

two or more alkenes may be generated by an E2 elimination, the more

stable alkene will be formed more rapidly and will therefore be the

predominant product. This is illustrated for 2-bromobutane by the energy

diagram on the right. The propensity of E2 eliminations to give the more

stable alkene product also influences the distribution of product

stereoisomers. In the elimination of 2-bromobutane, for example, we find

that trans-2-butene is produced in a 6:1 ratio with its cis-isomer.

The Zaitsev Rule is a good predictor for simple elimination reactions of

alkyl chlorides, bromides and iodides as long as relatively small strong

bases are used. Thus hydroxide, methoxide and ethoxide bases give

comparable results. Bulky bases such as tert-butoxide tend to give

higher yields of the less substituted double bond isomers, a

characteristic that has been attributed to steric hindrance. In the case

of 2-bromo-2,3-dimethylbutane, described above, tert-butoxide gave a 4:1

ratio of 2,3-dimethyl-1-butene to 2,3-dimethyl-2-butene ( essentially

the opposite result to that obtained with hydroxide or methoxide). This

point will be discussed further once we know more about the the

structure of the E2 transition state.

Bredt's Rule

The importance of maintaining a planar configuration of the trigonal

double-bond carbon components must never be overlooked. For optimum

pi-bonding to occur, the p-orbitals on these carbons must be parallel,

and the resulting doubly-bonded planar configuration is more stable than

a twisted alternative by over 60 kcal/mole. This structural constraint

is responsible for the existence of

alkene stereoisomers when substitutuion patterns permit. It

also prohibits certain elimination reactions of bicyclic alkyl halides,

that might be favorable in simpler cases. For example, the bicyclooctyl

3�-chloride shown below appears to be similar to tert-butyl chloride,

but it does not undergo elimination, even when treated with a strong

base (e.g. KOH or KOC4H9).

There are six equivalent beta-hydrogens that might be attacked by base

(two of these are colored blue as a reference), so an E2 reaction seems

plausible. The problem with this elimination is that the resulting

double bond would be constrained in a severely twisted (non-planar)

configuration by the bridged structure of the carbon skeleton. The

carbon atoms of this twisted double-bond are colored red and blue

respectively, and a Newman projection looking down the twisted bond is

drawn on the right. Because a pi-bond cannot be formed, the hypothetical

alkene does not exist. Structural prohibitions such as this are often

encountered in small bridged ring systems, and are referred to as

Bredt's Rule.

Bredt's Rule should not be applied blindly to all bridged ring systems.

If large rings are present their conformational flexibility may permit

good overlap of the p-orbitals of a double bond at a bridgehead. This is

similar to recognizing that trans-cycloalkenes cannot be prepared if the

ring is small (3 to 7-membered), but can be isolated for larger ring

systems. The anti-tumor agent taxol has such a bridgehead double bond

(colored red), as shown in the following illustration. The

bicyclo[3.3.1]octane ring system is the smallest in which bridgehead

double bonds have been observed. The drawing to the right of taxol shows

this system. The bridgehead double bond (red) has a cis-orientation in

the six-membered ring (colored blue), but a trans-orientation in the

larger eight-membered ring.

2. Stereochemistry of the E2

Reaction

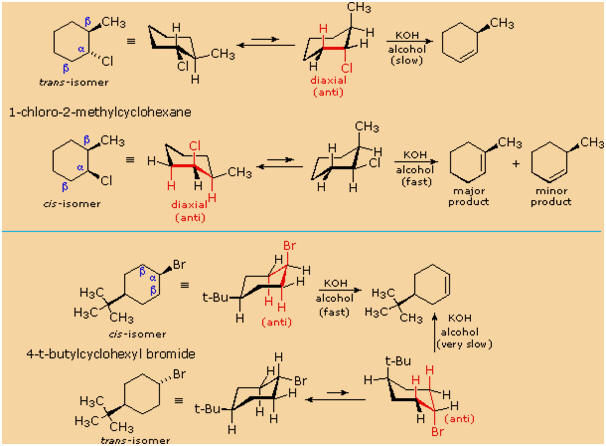

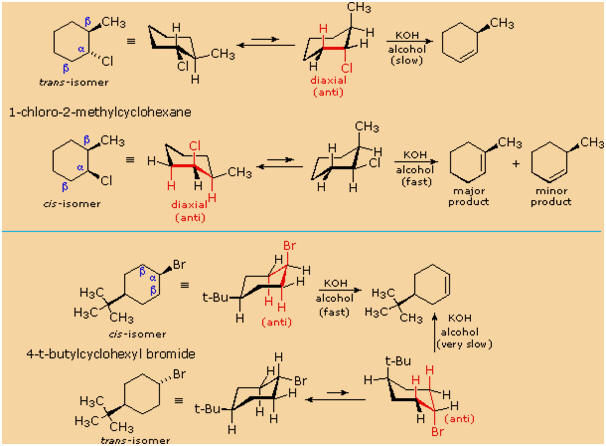

E2 elimination reactions of certain isomeric cycloalkyl halides show

unusual rates and regioselectivity that are not explained by the

principles thus far discussed. For example,

trans-2-methyl-1-chlorocyclohexane reacts with alcoholic KOH at a much

slower rate than does its cis-isomer. Furthermore, the product from

elimination of the trans-isomer is 3-methylcyclohexene (not predicted by

the Zaitsev rule), whereas the cis-isomer gives the predicted

1-methylcyclohexene as the chief product. These differences are

described by the first two equations in the following diagram.

Unlike open chain structures, cyclic compounds generally restrict the

spatial orientation of ring substituents to relatively few arrangements.

Consequently, reactions conducted on such substrates often provide us

with information about the preferred orientation of reactant species in

the transition state. Stereoisomers are particularly suitable in this

respect, so the results shown here contain important information about

the E2 transition state.

The most sensible interpretation of the elimination reactions of 2- and

4-substituted halocyclohexanes is that this reaction prefers an anti

orientation of the halogen and the beta-hydrogen which is attacked

by the base. These anti orientations are colored in red in the above

equations. The compounds used here all have six-membered rings, so the

anti orientation of groups requires that they assume a diaxial

conformation. The observed differences in rate are the result of a

steric preference for

equatorial orientation of large substituents,

which reduces the effective concentration of conformers having an axial

halogen. In the case of the 1-bromo-4-tert-butylcyclohexane isomers, the

tert-butyl group is so large that it will always assume an equatorial

orientation, leaving the bromine to be axial in the cis-isomer and

equatorial in the trans. Because of symmetry, the two axial

beta-hydrogens in the cis-isomer react equally with base, resulting in

rapid elimination to the same alkene (actually a racemic mixture). This

reflects the fixed anti orientation of these hydrogens to the chlorine

atom. To assume a conformation having an axial bromine the trans-isomer

must tolerate serious crowding distortions. Such conformers are

therefore present in extremely low concentration, and the rate of

elimination is very slow. Indeed, substitution by hydroxide anion

predominates.

A similar analysis of the 1-chloro-2-methylcyclohexane isomers explains

both the rate and regioselectivity differences. Both the chlorine and

methyl groups may assume an equatorial orientation in a chair

conformation of the trans-isomer, as shown in the top equation. The

axial chlorine needed for the E2 elimination is present only in the less

stable alternative chair conformer, but this structure has only one

axial beta-hydrogen (colored red), and the resulting elimination gives

3-methylcyclohexene. In the cis-isomer the smaller chlorine atom assumes

an axial position in the more stable chair conformation, and here there

are two axial beta hydrogens. The more stable 1-methylcyclohexene is

therefore the predominant product, and the overall rate of elimination

is relatively fast.

An orbital drawing of the anti-transition state is shown on the right.

Note that the base attacks the alkyl halide from the side opposite the

halogen, just as in the SN2

mechanism. In this drawing the α and β carbon atoms are undergoing a

rehybridization from sp3

to sp2

and the developing π-bond is drawn as dashed light blue lines. The

symbol R represents an alkyl group or hydrogen. Since both the

base and the alkyl halide are present in this transition state, the

reaction is bimolecular and should exhibit second order kinetics. We

should note in passing that a syn-transition state would also provide

good orbital overlap for elimination, and in some cases where an

anti-orientation is prohibited by structural constraints syn-elimination

has been observed.

It is also worth noting that anti-transition states were preferred in

several addition reactions to alkenes, so there is an intriguing

symmetry to these inverse structural transformations.Having arrived at a

useful and plausible model of the E2 transition state, we can understand

why a bulky base might shift the regioselectivity of the reaction away

from the most highly substituted double bond isomer. Steric hindrance to

base attack at a highly substituted beta-hydrogen site would result in

preferred attack at a less substituted site.

To see the effect of steric hindrance at a beta carbon on the E2

transition state

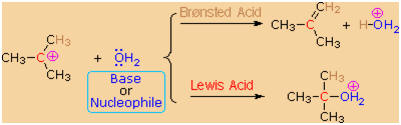

3. The E1 Reaction

Just as there were two mechanisms for nucleophilic substitution, there

are two elimination mechanisms. The E1 mechanism is nearly identical to

the SN1

mechanism, differing only in the course of reaction taken by the

carbocation intermediate. As shown by the following equations, a

carbocation bearing beta-hydrogens may function either as a Lewis acid

(electrophile), as it does in the SN1

reaction, or a Br�nsted acid, as in the E1 reaction.

Thus, hydrolysis of tert-butyl chloride in a mixed solvent of water and

acetonitrile gives a mixture of 2-methyl-2-propanol (60%) and

2-methylpropene (40%) at a rate independent of the water concentration.

The alcohol is the product of an SN1

reaction and the alkene is the product of the E1 reaction. The

characteristics of these two reaction mechanisms are similar, as

expected. They both show first order kinetics; neither is much

influenced by a change in the nucleophile/base; and both are relatively

non-stereospecific.

(CH3)3C�Cl

+ H2O

��>

[ (CH3)3C(+)

] +

Cl(�)

+ H2O

��>

(CH3)3C�OH

+ (CH3)2C=CH2

+ HCl + H2O

To summarize, when carbocation intermediates are formed one can expect

them to react further by one or more of the following modes:

1.

The cation may bond to a nucleophile to give a substitution product.

2. The cation may transfer a beta-proton to a base, giving an

alkene product.

3. The cation may rearrange to a more stable carbocation, and

then react by mode #1 or #2.

Since the SN1

and E1 reactions proceed via the same carbocation intermediate, the

product ratios are difficult to control and both substitution and

elimination usually take place.

Having discussed the many factors that influence nucleophilic

substitution and elimination reactions of alkyl halides, we must now

consider the practical problem of predicting the most likely outcome

when a given alkyl halide is reacted with a given nucleophile. As we

noted earlier, several variables must be considered, the most

important being the structure of the alkyl group and the nature of the

nucleophilic reactant. The nature of the halogen substituent on the

alkyl halide is usually not very significant if it is Cl, Br or I. In

cases where both SN2 and E2 reactions compete, chlorides generally give more

elimination than do iodides, since the greater electronegativity of

chlorine increases the acidity of beta-hydrogens. Indeed, although alkyl

fluorides are relatively unreactive, when reactions with basic

nucleophiles are forced, elimination occurs (note the high

electronegativity of fluorine).

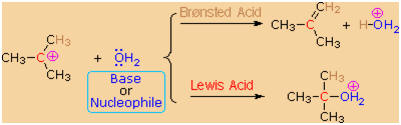

SN1 mechanism

SN1

indicates a substitution, nucleophilic, unimolecular reaction,

described by the expression rate = k [R-LG]

This

pathway is a multi-step process with the following characteristics:

-

step 1: rate

determining (slow) loss of the leaving group,

LG, to generate a carbocation

intermediate, then

-

step 2: rapid

attack of a nucleophile on the electrophilic carbocation to form a new σbond

|

|

Multi-step reactions have intermediates and a several transition

states (TS).

In an SN1

there is loss of the leaving group generates an intermediate

carbocation which is then undergoes a rapid reaction with the

nucleophile.

The reaction profiles

shown here are simplified and do not include the equilibria for

protonation of the -OH. |

|

|

General case |

|

SN1 reaction |

The

following issues are relevant to the SN1 reactions of alcohols:

Effect of R-

Reactivity order : (CH3)3C- > (CH3)2CH-

> CH3CH2- > CH3-

In an

SN1 reaction, the key step is the loss of the leaving group to form

the intermediate carbocation. The more stable the carbocation is, the easier it

is to form, and the faster the SN1 reaction will be. Some students

fall into the trap of thinking that the system with the less stable carbocation

will react fastest, but they are forgetting that it is the generation of the

carbocation that is rate determining.

-LG

The only event in the rate determining step of the SN1 is breaking

the C-LG bond. For alcohols it

is important to remember that -OH is a very poor leaving. In the reactions with

HX, the -OH is protonated first to give an oxonium, providing the much better

leaving group, a water molecule (see scheme below).

Nu

Since the nucleophile is not involved in the rate determining step of an SN1

reaction, the nature of the nucleophile is unimportant. In the reactions of

alcohols with HX, the reactivity trend of HI > HBr > HCl > HF is not due to the

nucleophilicity of the halide ion but the acidity of HX which is involved in

generating the leaving group prior to the rate determining step.

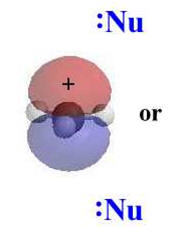

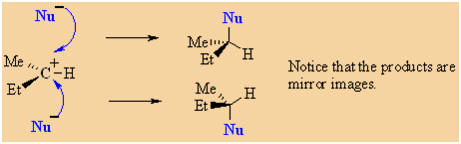

Stereochemistry

|

|

In an SN1, the nucleophile attacks the planar carbocation.

Since there is an equally probability of attack on either face there

will be a loss of stereochemistry at the reactive center and

both possible products will be observed.

|

Carbocations

Stability:

The general stability order of simple alkyl carbocations is: (most stable) 3o

> 2o > 1o > methyl (least stable)

This is because alkyl groups are weakly electron donating due to

hyperconjugation and

inductive effects. Resonance effects can further stabilise carbocations

when present (delocalisation of charge is a stabilising effect).

Note that reactions that occur via 3o and 2o are

known. 1o cations have been observed under special conditions,

but methyl cations have never been observed.

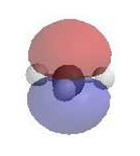

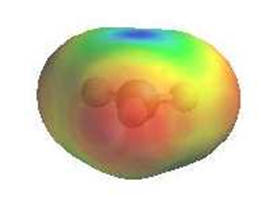

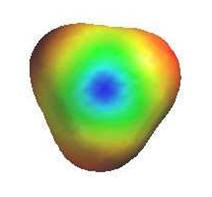

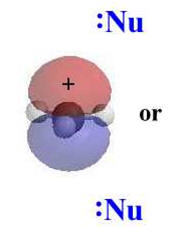

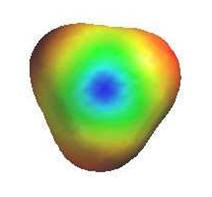

Structure:

|

|

Alkyl carbocations are sp2 hybridised, planar systems at

the cationic C centre.

The p-orbital that is not utilised in the hybrids is empty and is

often shown bearing the positive charge since it represents the

orbital available to accept electrons. |

|

Reactivity:

|

|

As they have an incomplete octet, carbocations are excellent

electrophiles and react readily with nucleophiles.

Alternatively, loss of H+ can generate a π bond.

The electrostatic

potential diagrams clearly show the cationic center in

blue, this is where the

nucleophile will attack.

|

|

Rearrangements:

Carbocations are prone to rearrangement via 1,2-hydride or 1,2-alkyl shifts if

it generates a more stable carbocation.

Hyper conjugation

Hyperconjugation

is the stabilising interaction that results from the interaction of the

electrons in a σ-bond (usually C-H or C-C) with an adjacent empty

(or partially filled) p-orbital or a π-orbital to give an extended molecular

orbital that increases the stability of the system.

Based on the

valence bond model of bonding, hyperconjugation can be described as "double bond

- no bond resonance" but it is not what we would "normally" call resonance,

though the similarity is shown below.

Hyperconjugation

is a factor in explaining why increasing the number of alkyl substituents on a

carbocation or radical centre leads to an increase in stability.

|

Let's

consider how a methyl group is involved in hyperconjugation with a

carbocation centre. |

|

|

First

we need to draw it to show the C-H σ-bonds.

Note that the empty p orbital associated with the positive charge at

the carbocation centre is in the same plane (i.e. coplanar)

with one of the C-H

σ-bonds (shown in blue.) |

|

|

This

geometry means the electrons in the σ-bond can be stabilised by an

interaction with the empty p-orbital of the carbocation centre.

(this

diagram shows the similarity with resonance and the structure on the

right has the "double bond - no bond" character) |

|

-

The

stabilisation arises because the orbital interaction leads to the electrons

being in a lower energy orbital

-

Of course,

the C-C σ-bond is free to rotate, and as it does so, each of the

C-H σ-bonds in turn undergoes the stabilising interaction.

-

The ethyl

cation has 3 C-H σ-bonds that can be involved in hyperconjugation.

-

The more

hyperconjuagtion there is, the greater the stabilisation of the system.

-

For example,

the t-butyl cation has 9 C-H σ-bonds that can be involved in

hyperconjugation.

-

Hence (CH3)3C+

is more stable than CH3CH2+

-

The effect is

not limited to C-H σ-bonds, appropriate C-C σ-bonds can also

be involved in hyperconjugation.

Inductive effects

-

An

inductive effect is an electronic effect due to the polarisation of σ

bonds within a molecule or ion.

-

In a

carbocation, the positive C attracts the electrons in the σ bonds towards

itself and away from the atom at the other end of the s bond.

-

Electrons in

C-C bonds are more readily polarised than those in a C-H bond.

-

Therefore,

alkyl groups are better at stabilising C+ than H atoms.

Go to Main Menu

-

© M.EL-Fellah ,Chemistry

Department, Garyounis University

|